The passage in 2 Samuel 21

follows King David's appeasement of the Gibeonites in order

to stop a famine. They request 7 of Saul's male descendants, and David

complies, and afterwards God as a result stops the famine. But wouldn't this be

a clear sign of the sins of the father affecting the sins of the son, which

goes against other areas of Scripture?

What I understand you to be asking is more precisely is about this:

“the punishment for the sins of the father being inflicted on the (non-complicit) sons (with or without it being borne by the father also)”

[We already know that the sins of a father almost always affects the well-being of their children—e.g. alcoholic parents. But this would never be considered ‘punishment’ on the children (unless the children were somehow intentionally complicit in the behavior)].

So, for example, in the case of David’s horrid actions vis-ŕ-vis Uriah and Bathsheba:

“Deuteronomy 24:16 lays down a general principle that human courts and human governments are not to impute to children or grandchildren the guilt of their parents or forebears when they themselves have not become implicated in the crime committed. It is clearly recognized in Scripture that each person stands on his own record before God.

Although this legal principle of dealing with each person according to his deeds is firmly laid down in Scripture, it is also made clear that God retained for Himself the responsibility of ultimate judgment in the matter of capital crime. In the case of the child conceived by Bathsheba of David when she was married to Uriah, the loss of that baby (in that Old Testament setting) was a judgment visited on the guilty parents for their gross sin (which actually merited the death penalty under Lev. 20:10). It is by no means suggested that the child was suffering punishment for his parents’ sin but that they were being punished by his death. [Gleason L. Archer, New International Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties (Zondervan’s Understand the Bible Reference Series; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1982), 152–153.]

The first point to make is that your understanding of the if-father-then-not-son principle is correct, but it was only instituted for HUMAN judicial cases:

“This is one of several laws in Deuteronomy that deal with judicial procedure rather than a specific crime.53 Although it is recognized in 5:9 that God punishes descendants for their ancestors’ wrongs, that is solely a divine prerogative: human authorities may not act likewise. That the verse here refers to execution by human judicial authorities is clear from the verb yumat, which always refers to judicial execution, not divine punishment. [Tigay, JPS Torah commentary on Deut]

“What is meant here, however, is a legal offense or “crime,” not “sin” in a theological sense. This is a law of judicial procedure (cf. 17:8–11; 19:15; 25:1–3). The thrice repeated passive formula denotes authorized, formal execution. Putting family members of a malefactor to death could stem from notions of collective guilt or as the punishment of a vicarious substitute for the actual offender. In Deuteronomy intergenerational collective responsibility does not apply in jurisprudence, although it is still assumed to operate in the wider realm of divine-human relationships (5:9; 7:10). This law is cited and obeyed in 2 Kgs 14:6. [Nelson, Deuteronomy]

This

protection of the sons (as well as the father, note) was unique in Israel:

“Elsewhere in ancient Near Eastern law, the notion that members of a man’s family were an extension of his own personality, rather than individuals in their own right, was sometimes taken to such an extreme that if a man harmed a member of another’s family, he was punished by the same harm being done to a member of his own family, often the corresponding member. At other times, an offender’s family might be punished along with him.55 While these were not necessarily universal practices, no explicit prohibition of them is known prior to Deuteronomy.56 There is, however, an implicit renunciation of the practice in Exodus 21:31, which rules that the owner of a goring ox is to be punished personally whether the ox gores an adult or a child; in other words, the owner’s child is not to be punished if the victim was a child. [Tigay]

“Deut. 24:16–18. Warning against Injustice.—V. 16. Fathers were not to be put to death upon (along with) their sons, nor sons upon (along with) their fathers, i.e., they were not to suffer the punishment of death with them for crimes in which they had no share; but every one was to be punished simply for his own sin. This command was important, to prevent an unwarrantable and abusive application of the law which is manifest in the movements of divine justice to the criminal jurisprudence of the lane (Ex. 20:5), since it was a common thing among the heathen nations—e.g., the Persians, Macedonians, and others—for the children and families of criminals to be also put to death (cf. Esther 9:13, 14; Herod. iii. 19; Ammian Marcell. xxiii. 6; Curtius, vi. 11, 20, etc.). An example of the carrying out of this law is to be found in 2 Kings 14:6, 2 Chron. 25:4. [Keil/Delitzch]

“There are various examples in the Code of Hammurabi (§§116, 209–10, 230 [COS, 2:343, 348–49]) and the Middle Assyrian Laws (§§50, 55 [COS, 2:359]) of children being executed or severely fined for the crime of their parent. [Grisanti, ExposBibComm,Numbers-Ruth]

So, if Saul had been a ‘regular’ citizen of Israel (and not a

ruler), if he murdered (or even committed manslaughter of) someone of

‘regular status’, only he could be punished.

In the case of murder or manslaughter, the victim’s family was responsible to send an ‘avenger of blood’ after them. The law was very clear – bloodshed pollutes the land and interferes with God’s stream of blessing on it. The only way to ‘cancel this out’ is by the blood/death of the perpetrator.

If this ‘avenger of blood could execute justice, then that would at least remove THAT single incident of blood pollution on the land.

[This was a crude way of keeping the ‘balance of power’ between the families and clans: if one ‘team’ lost an important member—giving the other team a one-person advantage –then the only way to get back to parity is by reducing the other ‘team’ by one of the same status. And the competitive metaphor is somewhat accurate, given the implicit competition for scarce resources and the power to influence distribution of those resources.]

If it was simple manslaughter, this need for compensatory ‘blood’ is still in force. The cities of refuge/asylum were a 'buffer’ for holding back YHWH’s rejection of the polluted land. The person committing the manslaughter had to remain in that safe-zone/buffer until the high priest died (whose blood –as a representative of the nation as a whole--counted for cancellation).

“These verses give the theological rationale for the penalties attached to taking human life. The shedding of blood pollutes (Hiphil of ḥānap̄) the land. The one who shed the blood (inadvertently) is kept confined in the city of refuge not only to keep him safe from the avenger of blood but also to keep the land isolated from the pollution of the act until the death of the high priest atones the shed blood and removes the bloodguilt. Both murder and inadvertent killing pollute the land. Murder is atoned for by the death of the murderer, inadvertent killing by the death of the high priest on behalf of the killer. Failing to observe these principles will defile (tammē’, lit., “make unclean”) the land. Defilement of the land would put the whole people into the realm of the unclean, which would be unthinkable because Yahweh himself (the Holy One of Israel) was dwelling in their midst. If the people allowed the land to be defiled, then holy Yahweh would no longer dwell in their midst, and they would be lost.”

[Timothy R. Ashley, The Book of Numbers (The New International Commentary on the Old Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1993), 656.]

And only blood/death did the cancellation. You could not take a money payment/fine as a substitute—for good reason:

“The principle is that shed human blood must be atoned for by shed human blood (Gen. 9:5–6; Exod. 21:12; Lev. 24:17; cf. Deut. 19:11–13). This principle is assumed here in two ways. First, it is forbidden for a ransom (kōp̄ēr) in money to be taken in place of the life of the convicted murder (i.e., by the procedures outlined above). The avenger of blood must carry out the sentence. ... The practical reason behind this law may very well be, as Noordtzij suggested, to avoid giving the rich who could afford such payments a loophole to commit murder at will, or a method of making an incident of human death an occasion for enrichment. The law thus upholds the principle of the importance of human life.”

[Timothy R. Ashley, The Book of Numbers (The New International Commentary on the Old Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1993), 655–656.]

If the perpetrator died however—by whatever means – the score was settled and the balance restored [and the unknown death of the perp was assumed to be orchestrated by the Lord to restore the balance.]

But blood (death) was required in any case.

And because the land was shared, there was an element of corporate responsibility – all persons were supposed to prevent murder—and this shows up in a couple of the laws about murder:

“In Israel bloodshed was said to pollute the land (Num. 35:33–34), and this bloodshed which defiles is said to have been “innocent blood” (Deut. 19:10; 21:8; 1 Ki. 2:5) that must be avenged (1 Ki. 2:31–33). “The guilt of bloodshed,” “the guilt of innocent blood,” and “guilt for blood” are mentioned. Yahweh informs his people that he will not listen when they offer their frequent prayers, because their hands are full of blood (Isa. 1:15). Judicial execution, killing in self-defense, and unintentional murder are excluded in the above considerations. (Cf. Exod. 22:2; Lev. 20:9; et al.) In the instance of the latter an ASYLUM must be provided for the person guilty of accidental homicide (Num. 35:9–34). If he leaves the asylum before the death of the high priest, he may be killed by the AVENGER OF BLOOD, who in such an instance is not guilty of murder (Num. 35:27). If a place of refuge is not provided for the unintentional killer and his blood is shed, the people are “guilty of bloodshed” (Deut. 19:10). [ZPEB]

And this ‘national guilt’ can be seen in the situation where a dead body is found out in a field, with no clue who the perp was. The elders of the closest towns had to make an oath that they knew nothing about it, but still had to offer a sacrifice in the location:

“Whenever homicide occurs, there is a sense in which the people corporately are guilty of bloodshed until justice has been satisfied (Deut. 21:1–9; Num. 35:33). If the guilty party is unknown, the elders and judges of the people shall determine which city lies closest to the place where the person was slain so that the priests and elders of that city may offer sacrifice and declare the innocence of their people. As they wash their hands over the sacrificed heifer they are to say: “Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it done. Accept this atonement for your people Israel, whom you have redeemed, O LORD, and do not hold your people guilty of the blood of an innocent man” (Deut. 21:7–8).[ZPEB, notice the scope—‘your people Israel’—not just the town]

But in no case would the children of the perp be prosecuted for the murder. They would be seriously affected by the event of course (including loss of status, loss of income, and perhaps some loss of legal standing)—but only as consequences and not as punishment for the parent’s crime.

And—if the defilement of the land via bloodshed was severe enough to trigger a famine-they would certainly be adversely affected by it (along with everyone else).

“Additionally, it should be noted that unatoned for blood is explicitly connected to the idea of famine and infertility in the land (Gen. 4:11–12; Num. 35:34; Deut. 21:1–9), thus strongly suggesting that this factor is of major importance in 2 Sam. 21:1–14 in which there is a famine in the land.”

[Joel S. Kaminsky, Corporate Responsibility in the Hebrew Bible (vol. 196; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 102–107.

There were

plenty of cases of bloodguilt that were not dealt with by Israel and/or

its leaders—and this could accumulate over time… eventually leading up the

exile.

Examples abound—Saul’s slaughter of the priests of Nob (and their city):

(1 Sam 22:16ff): “And the king said, “You shall surely die, Ahimelech, you and all your father’s house.” And the king said to the guard who stood about him, “Turn and kill the priests of the LORD, because their hand also is with David, and they knew that he fled and did not disclose it to me.” But the servants of the king would not put out their hand to strike the priests of the LORD. Then the king said to Doeg, “You turn and strike the priests.” And Doeg the Edomite turned and struck down the priests, and he killed on that day eighty-five persons who wore the linen ephod. And Nob, the city of the priests, he put to the sword; both man and woman, child and infant, ox, donkey and sheep, he put to the sword.”

Joab almost stands alone in how blatant his was:

“The first person on David’s list was Joab,

a close relative of David’s who had stood by him and fought for him in the most

difficult times of his rule. However, he had killed Abner (2:5a), the

commander of Israel’s army during the reign of Saul, just after Abner had

agreed to bring the army of Israel over to David (2 Sam 3:17–30). Later, David

had planned to replace Joab with Amasa as the commander of Israel’s army (2:5b;

2 Sam 19:13). Joab had effectively prevented this by killing Amasa while

he was carrying out the king’s orders. David had been forced to put up with

this ‘son of Zeruiah’ (2 Sam 19:21–23), but he knew that (their) shedding

innocent blood could bring disaster on the whole nation.”

[Tokunboh Adeyemo, Africa Bible Commentary (Nairobi, Kenya; Grand Rapids, MI: WordAlive Publishers; Zondervan, 2006), 418.]

The king Manasseh was a tipping point, in that he led the entire people into great sin, but also shed so much innocent blood (unatoned for). The exile was not just due to the king’s sin, but also those of the people he had turned to evil (and their complicity in his bloodshed). It was often worded as the ‘sins of Manasseh’ but this included all the corruption he created in the populace—as indicated by the terms ‘made to sin’ and ‘led them astray’ and it was the ‘they’ who did ‘more evil than the nations’, along with the king:

“Manasseh led them astray to do more evil than the nations had done whom the LORD destroyed before the people of Israel. … Because Manasseh king of Judah has committed these abominations and has done things more evil than all that the Amorites did, who were before him, and has made Judah also to sin with his idols…because they have done what is evil in my sight and have provoked me to anger… Moreover, Manasseh shed very much innocent blood, till he had filled Jerusalem from one end to another, besides the sin that he made Judah to sin so that they did what was evil in the sight of the LORD…Surely this came upon Judah at the command of the LORD, to remove them out of his sight, for the sins of Manasseh, according to all that he had done, and also for the innocent blood that he had shed. For he filled Jerusalem with innocent blood, and the LORD would not pardon.”

And sadly, the reforms of Josiah after him did not reach deep enough into the people to reflect a change of heart. They reverted the second the next king arrived

In some

mystical sense, blood had a life of its own. “Life is in the blood” and shed

blood had a voice, that called our

for peace through justice.

We see this in the earlies act of violence in the bible, when Cain killed Abel:

“And the LORD said, “What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to me from the ground.”

And as ‘unrequited’ violence increased in the land, those voices accumulated…

God delayed so much judgment that it is no wonder that later generations could believe that ‘our fathers sinned, but only we get the punishment’ (though they were just as guilty themselves).

………………………………………………………

But let’s back up now to see exactly the situation and the players.

“Now there was a famine in the days of David for three years, year after year. And David sought the face of the LORD. And the LORD said, “There is bloodguilt on Saul and on his house, because he put the Gibeonites to death.” 2So the king called the Gibeonites and spoke to them. Now the Gibeonites were not of the people of Israel but of the remnant of the Amorites. Although the people of Israel had sworn to spare them, Saul had sought to strike them down in his zeal for the people of Israel and Judah. 3And David said to the Gibeonites, “What shall I do for you? And how shall I make atonement, that you may bless the heritage of the LORD?” 4The Gibeonites said to him, “It is not a matter of silver or gold between us and Saul or his house; neither is it for us to put any man to death in Israel.” And he said, “What do you say that I shall do for you?” 5They said to the king, “The man who consumed us and planned to destroy us, so that we should have no place in all the territory of Israel, 6let seven of his sons be given to us, so that we may hang them before the LORD at Gibeah of Saul, the chosen of the LORD.” And the king said, “I will give them.” [ESV]

Elements:

1. Three years of famine in the land. One year of drought might be a common occurrence, but not 3.

2. This seems to have occurred late in David’s rulership period:

· “God had delayed this visitation until it would do the least possible damage to the security of the nation, that is, until after the surrounding nations had been defeated and subdued to the rule of King David.” [Gleason L. Archer, New International Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties (Zondervan’s Understand the Bible Reference Series; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1982), 152–153.

· “If the famine took place during the events described in 2 Samuel 8, when David and the men of Israel were fighting wars on all sides, then it is easy to see why it was only after three years that the king had the leisure time to inquire of the Lord the reason.” [Cyril J. Barber, The Books of Samuel: The Sovereignty of God Illustrated in the Life of David (vol. Two; Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 315–316.]

3. It was for the whole land (v 14), which would have included Gibeon, its satellite cities, and the locations of the families of Rizpah and Merab (probably still in the same vicinity, being Benjaminite). Their families would have suffered – along with the Gibeonites-- already for the 3 years, due to the as-then-unknown crime/judgement on their father/grandfather.

4. The actions against the Gibeonites must have happened much earlier, when Saul still had a significant army and before the final battle.

5. Up until the final battle in which Saul was killed, at least 3 of his ‘official’ adult sons (Jonahan, Malchi-shua, Abinadab) were doing military operations with him (which would have included anything against the Gibeonites).

6. The youngest son of the 4 might have not been involved in the final battle (or was assigned to a peripheral role)--Eshbaal/Ishbosheth—who is the de facto leader of the northern coalition in the subsequent civil war over kingship.

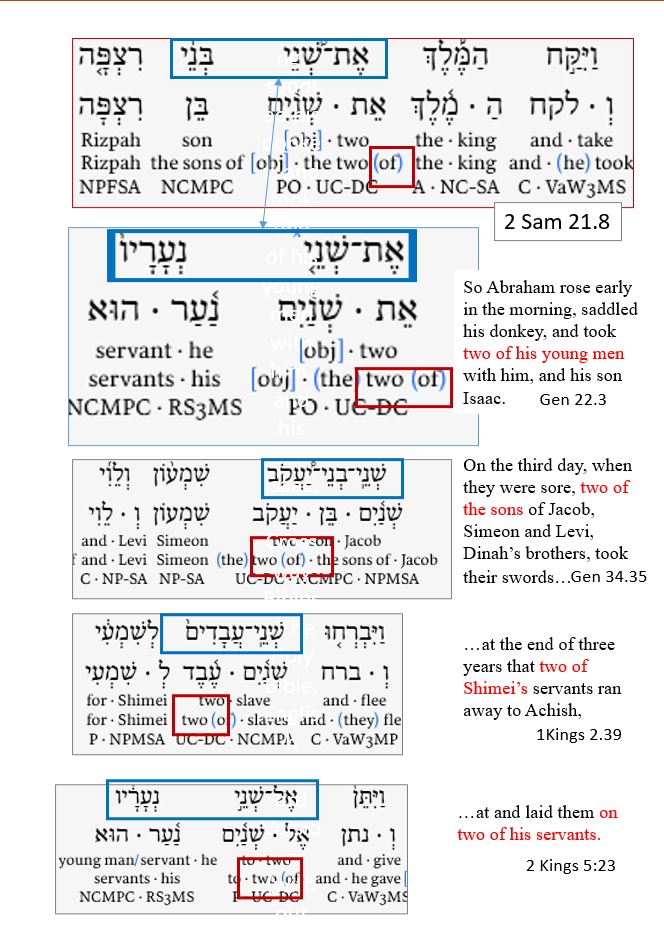

7. Although not legitimate heirs to the throne, there were at least two other sons of Saul in the same age range as the others, by one concubine (which shows up in this 2nd Samuel story). It would be unusual for a king to have had only one concubine at the time, so there might have been other sons as well. And depending on the date of their connection, Rizpah could have had other unlisted sons by Saul as well (the Hebrew construction could easily be translated as ‘two OF her sons which she bore to Saul’—see figure below—there is no ‘the’ in the phrase ‘the two sons’), before bearing children for her post-Saul husband. [All of the sons of Saul—including Rizpah’s two-- would have been expected to participate in military initiatives (including those against Gibeon) along with the ‘official’ sons.]

8. It would be reasonable to expect that Rizpah had other children with her post-Saul husband. And not having any Saulide blood in them, it would have omitted them from consideration. It would likely be they who provided food and water for her during her vigil over the dead bodies of her Saulide sons.

9. Saul’s sons would likely have already had male offspring before the final fatal battle [including these sones of of Rizpah], in the same cohort as Mephibosheth (who had male sons listed in the genealogies) [“So too Cazelles, who insists that Saul’s sons must have had male offspring (“David’s Monarchy and the Gibeonite Claim,” 172)”] If this famine event happened late in David’s career, by this time Mephibosheth already has sons (e.g.Mica), so there probably were grandsons of Saul, from the sons of the sons who perished in the battle. So we had

· cohort 1 (Saul’s sons, e.g. Jonathan, Ishbosheth, Rizpah’s sons),

· cohort 2 (Saul’s grandsons, e.g. Mephibosheth, sons of Rizpah’s sons, Merib’s sons), and

· cohort 3 (Sauls’ great-grandsons, e.g. Mica).

If—as expected since David did not do the ‘dynastic cleaning’ program—the sons of Saul in cohort 1 ALREADY had sons in cohort 2 before their death, then there would be many descendants of Saul in cohort 3.

10. So, there were probably many descendants/relatives of Saul still around at the time of this famine-maybe even surprised that they were not killed in the aftermath of David taking the throne, years earlier. And we do not know (except in the case of Mephibosheth) what their attitude toward David might have been, although there doesn’t seem to be any wholesale territory ‘grabs’ by David—if the situation of Mephibosheth is representative.

11. The Gibeonite violence was done INSIDE the territory of Israel and must have been when he was not (1) pursuing David; nor (1) when he was otherwise engaged with foreign enemies (i.e. a time of relative peace).

12. Nobody knew the cause of this famine—not even the Gibeonites—until David got the answer from the Lord about it being ‘bloodguilt’ and ‘against Gibeon’ by Saul and his family, in the distant past.

13. This violence was stated to be quite strong: it was ‘bloodguilt for putting the Gibeonites to death’, indicating that there was a victim group whose needs and/or appeals to the Lord were unmet.

14. David would have known that the Gibeonites were a ‘protected people’ from both archival records and their constant presence at the holy places. The events of the book of Joshua were often remembered in the Psalms (some written by David) and Prophets. And anything even semi-legal was recorded/remembered with precision (e.g. Joshua’s curse on the rebuilder of Jericho, remembered and cited in the time of Elijah and Ahab, 1 Kings 16:34; the judgment on Eli in 1st Samuel 2 referred to in1st Kings 2, relative to Abiathar).

15. The Lord didn’t give directions to David as to how to remedy the situation (though David knows that bloodguilt requires compensatory bloodshed for neutralization, so he might have been anticipating something along these lines—but of a much larger scale than what happened).

The text

then fills in the underlying reason for why this action of

Saul and his family was particularly evil—the violation of a sacred

treaty.

· Gibeon was one of 4 cities just north of Jerusalem, and very close to the Gibeah of Benjamin—Saul’s homeplace and center of his government. They lived in the territory allotted to Benjamin.

· At the beginning of the period of the Conquest under Joshua, Gibeon was a powerful city (like a’ royal city’, since it had a couple of satellite towns under its dominion—Joshua 10). It used deception to get the leaders of Israel to make a covenant of alliance with them (Joshua 9). And even though the populace wanted to destroy them, the tribal leaders were explicit in why they should not:

“At the end of three days after they had made a covenant with them, they heard that they were their neighbors and that they lived among them. 17And the people of Israel set out and reached their cities on the third day. Now their cities were Gibeon, Chephirah, Beeroth, and Kiriath-jearim. 18But the people of Israel did not attack them, because the leaders of the congregation had sworn to them by the LORD, the God of Israel. Then all the congregation murmured against the leaders. 19But all the leaders said to all the congregation, “We have sworn to them by the LORD, the God of Israel, and now we may not touch them. 20This we will do to them: let them live, lest wrath be upon us, because of the oath that we swore to them.” 21And the leaders said to them, “Let them live.” So they became cutters of wood and drawers of water for all the congregation, just as the leaders had said of them.

· The covenant was binding on all Israel—including the populace-- as negotiated by the leaders. Everyone knew that a treaty sworn in the name of YHWH would have disastrous consequences if violated (easily detected in the fear in the statements by the elders). Not only would they be guilty of taking the Lord’s name in vain (oath), but also of violating a national treaty. Any Israelite (regardless of status or role) who did violence to the Gibeonites would have violated a national treaty, and potentially would trigger the covenant penalties.

“However, the leaders of Israel shrank from breaking their oath, not because they assumed that it had an absolute binding force, but because they had sworn it by Yahweh, the God of Israel (9:19). Breaking this oath would bring the name of Yahweh into contempt among the Canaanites, and would also make the Israelites guilty of breaking God’s command not to use his name in vain. They were therefore bound to observe the oath, if only to preserve the integrity of the God by whom they had sworn. [Tokunboh Adeyemo, Africa Bible Commentary (Nairobi, Kenya; Grand Rapids, MI: WordAlive Publishers; Zondervan, 2006), 279–280.]

·

Historically, Gibeon had been faithful

covenant keepers and allies.

¨ Their ‘curse’ was to be doing menial tasks for Israel, but especially at the altar of God. Before Solomon built the temple, the most sacred place was in Gibeon, and these people would have been around the Lord’s presence all the time:

o (9: 27) “But Joshua made them that day cutters of wood and drawers of water for the congregation and for the altar of the LORD, to this day, in the place that he should choose”.

o “These con men, even though slaves, found themselves serving at the very altar of God because of Israel’s blunder!” [Tokunboh Adeyemo, Africa Bible Commentary (Nairobi, Kenya; Grand Rapids, MI: WordAlive Publishers; Zondervan, 2006), 279–280.]

¨ Their very presence (as non-Israelites) as servants at the tabernacle, ark, and altar would have been a constant reminder to everyone of the sacred treaty and the Gibeonites faithfulness to THEIR responsibilities under it.

¨ Gibeon was a Levitical city, also exposing them to more of the Lord’s influence (Josh 21.17).

¨ It was an important spiritual center for Israel, and the servants would have been part of those events, witnessed oaths, heard blessings and curses, and seen sacrifices.

“It is noted in 1 Kings that the people were sacrificing at the high place at Gibeon, that Solomon offered one thousand burnt offerings on the altar there, and that Solomon’s famous inaugural dream occurred at the high place at Gibeon (1 Kings 3:1–15). According to 1 Chronicles 16:39; 21:29, the ‘tabernacle’ (miškān) also was there.

…

“Based on the textual material, S. Shalom Brooks argues that Gibeon played an important role in Israelite cultic life before Solomon—that is, since the time of Saul. First, it is implausible that Gibeon was insignificant throughout the period between Samuel and Saul and David; its cultic popularity does not make sense unless the sanctuary had a long history behind it. Second, the description of worship at Gibeon makes sense and is convincing because Gibeon is also described as a Levitical city (Josh 21:17). This view may be supported by the work of J. Blenkinsopp (1974), who proposed that the sanctuary that David visited (2 Sam 21:1) was at Gibeon, and that the first altar that Saul built to Yahweh (1 Sam 14:33) was in the Gibeonite region and must be the great stone (hāʾeben haggĕdôlâ) at Gibeon (2 Sam 20:8). This story has cultic significance (Josh 24:26; 1 Sam 6:14–16) and may be identified with the altar on which Solomon offered sacrifices (1 Kings 3:4). “

[S. Shalom Brooks, “Gibeon,” ed. Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson, Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 332–333.]

“Then 1 Kgs 3 (…) describes Gibeon as the great “high place” of the period before Solomon built the Jerusalem temple: Solomon offers vast sacrifices and receives a night vision there (recalled above at 2 Sam 20:8). “

[A. Graeme Auld, I & II Samuel: A Commentary (ed. William P. Brown, Carol A. Newsom, and Brent A. Strawn; 1st ed.; The Old Testament Library; Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012), 571–575.]

¨ They assisted in the rebuilding of the city wall of Jerusalem (Neh 3:7] and they are generally considered to be part of the group known as ‘temple servants’ throughout Israel’s history, and some of which actually went into exile with them.

¨ “Interestingly, a Gibeonite soldier (Ishmaiah), was over David’s thirty mighty men (cf. 1 Chr 12:4)

¨ They did not take ‘Benjamin’s’ side in the post-Saul conflict against David (even though they lived inside the Benjamin territory and surrounded by Benjaminites):

o “Gibeon appears to have been neutral in the civil war between Ishbosheth and David (cf. 2 Sam 2 and 20:8). There can be no doubt that this act solidified an important political bond between the Gibeonites and David and ultimately Solomon.” [Brian Neil Peterson, “The Gibeonite Revenge of 2 Sam 21:1–14: Another Example of David’s Darker Side or a Picture of a Shrewd Monarch?,” Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament 1 (2011–2012): 201–218.]

¨ Interestingly, some of this proximity to the Lord rubbed off on them, for their wording and request show a deep reverence for sacred ritual and ‘reasonableness’(if not ’mercy’) in thei request.

This treaty would have been like most treaties back then, with responsibilities, penalty clauses, a witness, and an enforcer.

“Oaths in

ancient Israel held to a specific literary form that routinely included a

curse upon oneself if he or she should happen to violate the oath. The

typical form is this: “Thus and more may God do to me/you, if I/you do/do not

so and so.”

…

“The full

form may occur, as in Eli’s adjuration to Samuel: “May God do so to you and

more also, if you hide anything from me of all that he told you!” (1 Sam 3:17).

Likewise, when Israel’s king swore to do away with Elijah in 2 Kgs 6:31, he

used this typical form: “So may God do to me, and more, if the head of Elisha

son of Shaphat stays on his shoulders today.”

…

“Thus, the

anticipation of divine wrath toward oath breakers is an inherent form of the

oath itself, and any oath made by Joshua and Israel’s tribal elders would

have shared this same basic format. David, then, would not be surprised to

learn that Israel’s plight was connected to the breaking of an oath; that is the way oaths work.”

[Tony W. Cartledge, 1 & 2 Samuel (ed. Samuel E.

Balentine and P. Keith Gammons; Smyth & Helwys

Bible Commentary; Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys

Publishing, Incorporated, 2001), 637–639.]

And

“A treaty such as this one would have been ratified by an

oath that invoked curses upon each nation involved in the agreement as a

corporate entity. These curses would have been backed up by the gods of

both nations, who are called upon to punish either

offending nation. And, of course, one of the usual punishments for a

covenantal violation is a famine, especially because a

famine can function as an omen that would force the guilty party to see his

error and repent. The notion that a famine can function as a type of alarm to

notify a population of a covenantal breach is an idea that occurs several times

in the Hebrew Bible (Lev. 26:18–20; Deut. 11:17; Amos 4:6–9). [Joel S. Kaminsky, Corporate Responsibility in the Hebrew Bible (vol. 196; Journal for

the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic

Press, 1995), 108–110.]

And

“The

making of a treaty in Israel inherently invoked Yahweh as witness to the

covenant and potential executor of punishment for violators. Many persons

suffered in the famine [note: and some probably died] during David’s day who

had nothing to do with Saul’s transgression of the ancient oath. [Tony W.

Cartledge, 1 & 2 Samuel (ed.

Samuel E. Balentine and P. Keith Gammons; Smyth & Helwys

Bible Commentary; Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys

Publishing, Incorporated, 2001), 645–646.]

The Gibeonites were probably surprised by David’s summons (v2). But when he mentions the violence of Saul against them and the need for justice, they quickly remember.

The text describes the actions of Saul using these terms:

· “he put the Gibeonites to death” (The Lord)

· “Although the people of Israel had sworn to spare them, Saul had sought to strike them down” (the narrator)

· “consumed us” (Gibeonites)

· “planned to destroy us” (Gibeonites)

· “leave us no place to live in all the territory of Isreal” (Gibeonites)

The event itself is not recorded, but commentators give some plausible scenarios:

· “According to v 2 this incident had been occasioned by Saul’s zeal for the people of Israel and Judah but its exact nature is not described. Schunck (Benjamin, 131–38) has well argued that Saul wished to annex Gibeon to make it into his new capital since his native Gibeah was not really suitable for this purpose.

[A. Anderson, 2 Samuel (vol. 11; Word Biblical Commentary; Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1989), 248–252.]

· “The statement in 21:2 that he acted in “zeal for Israel and Judah” suggests that the action was an expression of some sort of extreme nationalism. The fact that the Gibeonites lived near Saul’s hometown of Gibeah and in the tribal territory of Benjamin may have exacerbated his disdain for them.

[J. Robert Vannoy, Cornerstone Biblical Commentarya: 1-2 Samuel (vol. 4; Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2009), 396–399.

· [T]he Benjamites had benefited from the land left vacant by the Gibeonites and had never repented of Saul’s crime nor sought to make any form of redress.”

[Cyril J. Barber, The Books of Samuel: The Sovereignty of God Illustrated in the Life of David (vol. Two; Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 316–317.]

· “Gibeon was close to Gibeah, Saul’s city, and had a famous shrine at which Solomon offered inaugural sacrifices when he became king (1 Kgs 3:4). Saul in his zeal resented the permission given to foreigners, Amorites, to serve even in a menial way at the shrine of the Lord (Josh. 9:27), and therefore put some Gibeonites to death.” [ Joyce G. Baldwin, 1 and 2 Samuel: An Introduction and Commentary (vol. 8; Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries; Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 302–30]

· [Note also that Saul’s great-grandfather was known as the ‘father of Gibeon’ (1 Chr 8:29-33; 9:35-39), so there might have been a desire to ‘reclaim’ some family territory that was thought to be theirs.]

· Most commentators struggle with the statement “in his zeal for the children of Israel and Judah.” The most plausible explanation is that this act of misguided “zeal” followed one of Samuel’s rebukes of him for not following the counsel of the Lord. Smarting under what he believed was undeserved criticism, he sought to show his concern for the purity of God’s people by removing these Amorites (21:2) within Israel from the face of the earth. They were defenseless and fell as easy prey to his evil scheme.

… But were Saul’s motives altruistic? William G. Blaikie raises another important question. Referring back to 1 Samuel 22:7, he asks: “From whence did Saul obtain the houses and lands that were given to his court officials?” And the answer: Most likely from the Gibeonites, for their territory lay within the borders assigned to the tribe of Benjamin.13 If Dr. Blaikie is correct, then Saul’s desire to preserve the genetic purity of his people was so much window dressing.

[Cyril J. Barber, The Books of Samuel: The Sovereignty of God Illustrated in the Life of David (vol. Two; Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 318–319.

· On this last point, land grabs by a new ruler was ‘the practice’.

Samuel had warned Israel about how a king would act when he came to power (1 Sam 8:11-17):

“He said, “These will be the ways of the king who will reign over you: he will take your sons and appoint them to his chariots and to be his horsemen and to run before his chariots. 12And he will appoint for himself commanders of thousands and commanders of fifties, and some to plow his ground and to reap his harvest, and to make his implements of war and the equipment of his chariots. 13He will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers. 14He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive orchards and give them to his servants. 15He will take the tenth of your grain and of your vineyards and give it to his officers and to his servants. 16He will take your male servants and female servants and the best of your young men [1] and your donkeys, and put them to his work. 17He will take the tenth of your flocks, and you shall be his slaves.

And when Saul was still actively trying to kill David, he used that thought in his arguments (1 Sam 22:7):

“Hear now, people of Benjamin; will the son of Jesse give every one of you fields and vineyards, will he make you all commanders of thousands and commanders of hundreds,

[Note here that David did not continue this practice himself. After Saul’s death, he gave Saul’s immediate belongings to his grandson Mephibosheth, and these belongings were later split between Mephibosheth and Saul’s servant Ziba. The belongings of Ishbosheth – at his demise—presumably stayed either with the current owners, or were included in the grant to Mephibosheth.]

So, Saul’s

actions in directing his army and his family to attempt to eradicate the

protected Gibeonites created more than just a large amount of bloodguilt

on his family (which required execution or sacrifice if the perp was not

available). These actions constituted the NATION as A TREATY VIOLATOR.

The king was known as the representative of the entire nation, and what he DID was considered national actions (for good or bad).

For example, when David pursed the Census – in spite of hearty counsel by his subordinate to desist – that resulted in a massive plague, that was only halted by sacrifice. [But note that it was ultimately triggered by Israel’s sins—"Again the anger of the LORD was kindled against Israel, and he incited David against them, saying, “Go, number Israel and Judah.”. The causal chain in here is obscure to me, and probably omits much background and even some steps.]

This event with Saul’s family/army appeared very similar:

· “Furthermore, it is not simply a matter of one Israelite who broke the treaty and mistreated the Gibeonites. It is Saul, who as king is representative of the nation as a whole. That the king’s actions can bring about either positive or negative consequences on the nation as a whole is a given within the ancient Near East. That this holds true of Israel as well is easily demonstrated by the fact that it is the new king, David, who is responsible for putting an end to the famine that is currently afflicting the nation as a whole due to the past misdeeds of the last king, Saul [[Joel S. Kaminsky, Corporate Responsibility in the Hebrew Bible (vol. 196; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 108–110.]

· “In the case of King Saul’s grandchildren, no ordinary crime was involved. It was a matter of national guilt on a level that affected Israel as a whole. We are not given any information as to the time or the circumstances of Saul’s massacre of the Gibeonites, but we are told that it was a grave breach of a covenant entered into back in the days of Joshua and enacted in the name of Yahweh (Josh. 9:3–15). All the nation was bound by this oath for all the days to come, even though it had been obtained under false pretenses. Therefore when Saul, as head of the Israelite government, committed this atrocity against the innocent Gibeonites, God saw to it that this covenant violation did not go unpunished. He sent a plague to decimate the population of all Israel, until the demands of justice could be met.

[Gleason L. Archer, New International Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties (Zondervan’s Understand the Bible Reference Series; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1982), 152–153.]

· “Davis (1999:222) suggests that the transgenerational punishment prohibition of Deut 24:16 “regulated individual criminal cases.” Saul’s offense against the Gibeonites was not “individual” but rather “national.” The oath sworn to the Gibeonites during the time of Joshua represented the entire nation and entailed a corporate responsibility. Tigay (1996:227) points out that the “few instances where punishment of children was legally sanctioned were not criminal cases but those involving offenses against God, such as violations of the kherem […] and national oaths.” [J. Robert Vannoy, Cornerstone Biblical Commentarya: 1-2 Samuel (vol. 4; Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2009), 396–399.]

· “Contrary to the provisions of this treaty, which had been sworn in the name of Yahweh, the God of Israel (Josh 9:15, 19), Saul had taken the lives of many Gibeonites in an attempt to eradicate them from the land.2 The result was that Israel now stood under the Lord’s curse rather than his blessing. Saul’s murder of Gibeonites had not only polluted the land (cf. Num 35:30–34) but had also invited whatever curses may have been attached to the treaty with the Gibeonites as well as those of Leviticus 26:20 and Deuteronomy 28:18 for taking the name of Yahweh in vain.” [J. Robert Vannoy, Cornerstone Biblical Commentarya: 1-2 Samuel (vol. 4; Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2009), 396–399.]

· “But whatever may have been Saul’s motive, it is certain that by his attempt to massacre and banish the Gibeonites a great national sin was committed, and that for this sin the nation had never humbled itself, and never made reparation. [Cyril J. Barber, The Books of Samuel: The Sovereignty of God Illustrated in the Life of David (vol. Two; Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 318–319.]

· “Saul’s guilt, then, is not the result of shedding blood as such—he shed the blood of many peoples—but of shedding the blood of a people protected by treaty oaths. [A. A. Anderson, 2 Samuel (vol. 11; Word Biblical Commentary; Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1989), 248–252.]

The treaty

required Israel to ‘protect’ the Gibeonites.

When Saul’s began the attempt to exterminate the Gibeonites, the rest of Israel should have ‘protected’ the Gibeonites. They should have refused to fight in that military action.

That would not have been unheard of, since we have cases of ‘non-compliance’ elsewhere:

· The servants of Saul refused to kill the priests of Nob (1 Sam 22.17),

· The army refused to allow Saul to kill Jonathon (1 Sam 24.4-45), and

· Some of the sons of Korah refused to participate in his rebellion—and so survived (Numbers 26.11).

But we see no evidence of pushback in this case. The nation of Isreal (majority vote type thing) went along with this treaty violation.

There are

probably plenty of Saulides still living (as noted

above), in spite of the normal practice of new dynasties eliminating the people/power of previous

dynasties (both in Israel and the wider ANE). This elimination was tactical

(lifeboat ethics) not ‘punishment’ or even ‘vengeance’ David’s actions toward

Saul’s family are unusual (in a good way).

· “David’s mercy toward Mephibosheth was unusual in the context of the times. Normally, when a new king ascended the throne, his family would acquire all the land that had belonged to the former dynasty. We also know from the history of the Near East that members of a dethroned royal family were often treated severely. They might escape execution, but would certainly be stripped of all their possessions. Unfortunately, examples of this type of behaviour are still common in Africa. After a coup d’état, the new regime often confiscates the property of the officials of the former regime.

[Tokunboh Adeyemo, Africa Bible Commentary (Nairobi, Kenya; Grand Rapids, MI: WordAlive Publishers; Zondervan, 2006), 279–280.]

· “The killing of contenders to the throne when a dynasty changed hands or a new king came to the throne is present throughout the Hebrew Bible. E.g., Abimelech’s killing of his brothers (Judg 9:5); Absalom’s attempted destruction of David (2 Sam 15–18); Bathsheba’s fear of Adonijah (2 Kgs 1:11–12); Zimri’s killing of Baasha and his family (1 Kgs 16:11); Jehu’s extermination of Ahab’s family (2 Kgs 9–10); and Athaliah with the Judean royal line (2 Kgs 11:1). [Brian Neil Peterson, “The Gibeonite Revenge of 2 Sam 21:1–14: Another Example of David’s Darker Side or a Picture of a Shrewd Monarch?,” Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament 1 (2011–2012): 201–218.]

· “It was customary to neutralize the preceding dynasty by murdering all the male members (e.g., 2 Kings 10:1–17; 11:1–2) [A. Salvesen, “Royal Family,” ed. Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson, Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 846.]

· A special case of this occurred when a son succeeded his father, and then killed all his brothers (who might try to kill HIM). Cases like Abimelech and Athaliah come readily to mind. When Saul died and Ishbosheth took over, why did the nurse haul little Mephibosheth away—all the way to Transjordan? Was she wise in assuming that Ishbosheth might do housecleaning? No reason is given for the flight of Mephibosheth, but that is the likeliest of scenarios.

Some leaders applied this to ANY hierarchy – not just dynastic. Rebels against authority (as opposed to 'common criminals’) were especially problematic, since they INTENDED to DISRUPT the community life. Rebels were a special class of offenders (as major social disruptors), with full impact on family:

“The proverb that occasioned this oracle [in Ezek, sons being punished for the sins of the father] was not peculiar to the exiles but was current in Jerusalem as well (Jer 31:29–30). It expressed resentment against the notion that a man’s family might be punished for his misdeeds, as though they were extensions of him, and mortgaged for his good behavior. This notion governed the treatment of rebels against human and divine authority in Israel and outside it. The practice is vividly described in the Hittite “Instructions for Temple Officials”:

… if a slave causes his master’s anger, they either kill him or they will injure him … or they will seize him, his wife, his children, his brother, his sister, his in-laws, his kin … If ever he is to die, he will not die alone; his kin will accompany him. If then … anyone arouses the anger of a god, does the god take revenge on him alone? Does he not take revenge on his wife, his children, his descendants, his kin, his slaves, and slave-girls, his cattle (and) sheep together with his crop, and will utterly destroy him? (ANET3, pp. 207–8; cf. also the plague prayer of Mursilis, ibid., p. 395, § 9)

In Israel, kings took such measures against [perceived] rebels (1 Sam 22:19 [Saul/Doeg against the priests and people of Nob]; 2 Kings 10:1–11 [Jesu against the 70 sons of Ahab]), as did Nebuchadnezzar against Zedekiah (2 Kings 25:7). A progressive ruling of Deut 24:16 outlawed the practice (…), and King Amaziah of Judah is cited as having spared the children of his father’s assassins in obedience to it (2 Kings 14:6). [Moshe Greenberg, Ezekiel 1–20]

Dynastic purges were the norm—they were expected and anticipated by the reigning family, but these are neither legal nor covenant/treaty related . But in the biblical texts the only purges sanctioned where those that involved offenses against God.

Only the purges of dynastic families are said to have been sanctioned by God, and this is due to the kings’ offenses against God directly (1 Kings 14:7–11; 16:1–14; 2 Kings 9:7–9) [Tigay]

“The Bible and other ancient sources mention cases of the execution of the entire family of those guilty of treason, as well as the families of kings whose dynasties were overthrown. This was probably done for tactical reasons, and in any case is not represented as legal. Indeed, we hear from time to time of kings who spared the families of traitors, and 2 Kings 14:6 reports that, in accordance with this law, King Amaziah spared the children of his father’s murderers.” [Tigay]

But that David did not do this when he rose to power is obvious from both (1) the (definite) existence of the 7 persons involved in this episode [long after the death of Saul] and (2) the (very likely) presence of other Saulides as noted above. [And of course he didn’t kill off all his older brothers either.]

Everybody—including Saul’s family and army—KNEW that David would become king. Saul himself had admitted that publicly [see also 2 Sam 5.2 where the elders of the ‘northern kingdom’ admit this to David after Ishbosheth is dead, and Abner has been killed], and being afraid that David might do what ‘normal kings did’, he asked David to spare his family from this ‘dynastic house-cleaning’, to which David agreed in an oath.

“David’s refusal to take personal vengeance led Saul to see himself in a new light. He was not convicted by argument or by accusation but by the testimony of David’s life. He confessed: You are more righteous than I … You have treated me well, but I have treated you badly (24:17–19).

…

“Saul ended with an even more remarkable admission: I know that you will surely be king (24:20). He was not forced to admit this by physical combat but by humble kindness and service. Such service is what the church should be offering.

…

“Saul then began to plead with David

not to cut off my descendants

(24:21). David again in the grace of God and with love in his heart, promised

that he would not take vengeance on them. Unfortunately, this promise

was not kept to the letter, for David played a role in the killing of seven of

Saul’s male descendants (2 Sam 21:6, 8–9) [but see note

below].

“Saul’s words must have made a deep impression on all who were following him, confirming to them that David was the man God had raised to deliver Israel.

[Tokunboh Adeyemo, Africa Bible Commentary (Nairobi, Kenya; Grand Rapids, MI: WordAlive Publishers; Zondervan, 2006), 368.

And

“David may have been using a technicality in succession rights when he chose the two sons of Rizpah, a concubine of Saul. Choosing the children of a concubine would have allowed David to keep his earlier vow to Saul—namely that David would not cut off his offspring who could succeed Saul to the throne (cf. 1 Sam 24:22). In 1 Sam 24 the context leads one to believe that descendants who had a right to the throne is what is in view when David made his vow to Saul.30 What is more, the Chronicler’s failure to mention Rizpah’s children as “sons” of Saul (cf. 1 Chr 8:33; 9:39) seems to be in keeping with the view that the sons of a concubine were not viewed as full “sons” who could inherit (cf. also Judg 11:1–2). [Brian Neil Peterson, “The Gibeonite Revenge of 2 Sam 21:1–14: Another Example of David’s Darker Side or a Picture of a Shrewd Monarch?,” Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament 1 (2011–2012): 201–218.]

Note: Many commentators state/imply (as above) that David failed to fulfill this oath to Saul, based on the events of our passage in 2 Samuel. But this is not technically correct. David did NOT do the ‘cutting off’ in any sense of the word. As covenant justice-keeper, he gave them over to the Gibeonites for their famine-busting ritual execution. There was no ‘dynastic housecleaning’ of the type expected by Saul. And there is not the slightest hint that ‘vengeance’ (for Saul’s crimes against David) was involved.

The text is very clear in identifying the Gibeonites as the executioners”

“..let seven of his sons be given to us, so that we may hang them before the LORD at Gibeah of Saul … and he gave them into the hands of the Gibeonites, and they hanged them on the mountain before the LORD,

And the end of the episode (described below) shows that (1) there was no mention of ‘vengeance’ element by anyone, and that (2) in fact these descendants received honorable burials—after their ritual semi-sacrificial execution to fulfill covenant requirements.

So, when Saul made the request of David:

“Swear to me therefore by the LORD that you will not cut off my offspring after me, and that you will not destroy my name out of my father’s house.” 22And David swore this to Saul.[1 Sam 24.21-22]

David complied fully, and indeed satisfied the second part of the request by the honorable reburial of Saul and his sons and grandsons.

…………………………………….

The

David-Gibeonite exchange has some interesting elements:

One. David assumes responsibility for the crimes of his predecessor. As king, he is attempting to reverse the curse triggered by Saul in the distant past. This was expected of national leaders, as many commentators point to a Hittite exemplar:

“The biblical story of the Gibeonites’ revenge shares the historiographical outlook of the plague prayers of Muršiliš. The central figure in each account is a king who is trying to discover the cause of a national disaster—a famine, a plague—and thus a way to avert it. The two documents have a common doctrine of causality which traces the present-day disaster to a past violation of treaty oaths. The famine arose in Israel because the former king, Saul, violated the oath sworn to the Gibeonites in the days of Joshua. The plague broke out in Hatti in consequence of the former king’s violation of the oath sworn in ratification of a peace treaty with Egypt. In each case it fell to the succeeding king to find the means of restitution for these past crimes. In each case the god before whom the oaths of ratification were sworn—Yahweh, the Hittite storm god—had to be appeased.

[P. Kyle McCarter Jr, II Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes, and Commentary (vol. 9; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 437–446.]

“This case in fact has a close resemblance to the case discussed in Mursilis’s plague prayer.50 A plague is raging in Hatti land and Mursilis discovers that one of its prime causes is that his father Suppiluliumas broke a treaty with the Egyptians, and thus angered the Hattian storm god who witnessed the signing of that treaty. As the new king he has both inherited the guilt of his father’s misdeeds and he, as the peoples’ mediator between them and the gods, is the party who is responsible for appeasing the deity and putting an end to the plague. Malamat concisely summarizes the affinities between Mursilis’s plague prayer and 2 Sam. 21:1–14:

It does not seem to have mattered how much time elapsed between the conclusion of a treaty and its violation; nor that the effect of the sin may have occurred a considerable time later, even after the death of the king who violated the treaty. In any case the transgression was not absolved with the death of the guilty king. In both sources, the Hittite and the Biblical, the guilt was laid to a king, who, as representative of the entire people, seems to have been held responsible for a disaster of national proportion.51[1]

[Joel S. Kaminsky, Corporate Responsibility in the Hebrew Bible (vol. 196; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 108–110.

“Malamat’s treatment brings into focus the central issue of a past crime transmitting its burden of guilt to the present generation. He succeeds in locating this issue within a known tradition of ancient Near Eastern historiography. He is able to demonstrate a common doctrine of causality in Hittite and Israelite literature according to which a national disaster (famine, plague, etc.) might arise from a past violation of a treaty oath. The primary Hittite texts are the so-called “plague prayers” of the fourteenth-century king Muršiliš II (ANET3, pp. 394–96). These prayers, addressed to the Hittite storm god, describe a severe plague that has been raging in Hatti for years. Muršiliš says that he has consulted an oracle and learned the cause of the plague. During his father’s reign there was a peace treaty between Hatti and Egypt sanctioned by oaths to the Hittite storm god. His father violated this treaty by repeatedly attacking Egyptian troops. The plague first broke out among prisoners brought back from one of these raids, and it has been ravaging Hatti ever since. Muršiliš now hopes to avert the scourge by admitting his guilt. “It is only too true,” he says, “that man is sinful. My father sinned and transgressed against the word of the Hattian Storm-god, my lord. But I have not sinned in any respect. It is only too true, however, that the father’s sin falls upon the son. So, my father’s sin has fallen upon me.” Muršiliš also mentions his propitiatory offerings and, with reference to the innumerable Hittites who have died in the plague, offers to make any kind of further restitution the storm god might require. [Brian Neil Peterson, “The Gibeonite Revenge of 2 Sam 21:1–14: Another Example of David’s Darker Side or a Picture of a Shrewd Monarch?,” Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament 1 (2011–2012): 201–218.]

“The Biblical story of the Gibeonites’ revenge shares some similarities with this ancient prayer. In each case there was a form of disaster (famine, plague) that threatened the well-being of the people. In each case the reason was a broken treaty, deliberately violated by the central figure—a king, now deceased. And in each case the new king was left to grapple with the problems left over from the previous administration.

[Cyril J. Barber, The Books of Samuel: The Sovereignty of God Illustrated in the Life of David (vol. Two; Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 317–318.

Two: He is asking about making atonement TO the Gibeonites (not to God). Atonement to God could be done without involving the Gibeonites at all, so their involvement is critical. In fact, this atonement is to satisfy the Gibeonites’ legitimate request for justice, so that they will ‘bless’ the heritage of the Lord.

David is asking them simply this: “What can I do as king of Israel to satisfy you to the point that you can pray for the land and its people”. [Remember, they are suffering from the famine as well…as well as social shame induced by Saul’s attempting to ‘rid the land of them’.]

“David pursues reconciliation with the Gibeonites “so that you will bless [an imperative used in a voluntative sense ‘for the purpose of expressing with somewhat greater force the intention of the previous verb’ (Driver, 350); cf. precisely the same construction—with the same verbal root—in Gen 12:2: ‘and (= so that) you will be a blessing’] the Lord’s inheritance” (i.e., the land and people of Israel. David apparently wants the Gibeonites, when their requirements have been met, to pray that God will bless David’s people. [Ronald F. Youngblood, “1, 2 Samuel,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: 1 Samuel–2 Kings (Revised Edition) (ed. Tremper Longman III and David E. Garland; vol. 3; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009), 3559–564.

“David did not suggest what should be done to atone for this evil. Instead he asked the Gibeonites what should be done to appease their anger and remove the curse from his kingdom (21:3). … He acceded to the Gibeonites’ request, thus restoring the covenant between Israel and Gibeon. . [Tokunboh Adeyemo, Africa Bible Commentary (Nairobi, Kenya; Grand Rapids, MI: WordAlive Publishers; Zondervan, 2006), 405–406.]

“Now that the Lord had revealed the cause of the curse, David met with the Gibeonites to determine a means of turning it aside. Though they were Israel’s virtual slaves (cf. Josh 9:27), David placed himself at the Gibeonites’ mercy by asking what he could do “to atone [from kāpar; NIV, “make amends”] so that they [NIV, “you”] will bless the Lord’s inheritance” (v. 3). David’s request subtly referenced the Abrahamic blessing (cf. Gen 12:3): the king could not bring a blessing to the Gibeonites; but as the Gibeonites’ attitude toward Israel changed to one of blessing, the Lord himself would bless the Gibeonites.9 [Robert D. Bergen, 1, 2 Samuel (vol. 7; The New American Commentary; Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 444–447.]

Three: The atonement word used can be understood a ‘monetary recompense’ (but rarely), and the first phrase of the Gibeonite response is about money (so they understood this potential aspect). The second phrase shows that they were not looking for blood-vengeance, since they were not under the Israelite legal system. Their final answer reflects the ‘let the evil done be done to the evil doer’ – common motif in biblical justice [Deut 19:18-19: “The judges shall inquire diligently, and if the witness is a false witness and has accused his brother falsely, then you shall do to him as he had meant to do to his brother.”] Saul tried to eradicate their entire community (multiple ‘houses’), so it would be fitting for justice to do the same to his ‘house’.

Four: In light of the extensive slaughter of the Gibeonites, it is very surprising that they asked only for 7 of his descendants to be ‘hung before the Lord’.

“The fact that the Gibeonites declined to receive any monetary compensation and asked only for a token judgment against Saul’s house may have come as a surprise to David. Only seven lives were to be forfeited. Seven is regarded as the perfect number in the Near East, and these seven victims will betoken a full and adequate judgment, for they are to be executed before the Lord to expiate His displeasure. [Cyril J. Barber, The Books of Samuel: The Sovereignty of God Illustrated in the Life of David (vol. Two; Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 318–319.]

Seven would only be a symbolic number, because Saul and his family would have killed many more of the Gibeonites (including children like the sons of Merob). The Gibeonites were not asking for ALL of Saul’s descendants to be delivered over to them for execution.

· “The number seven represents a full number (seven symbolizing completeness) even though many more Gibeonites had been slain by Saul, since we are told he “had tried to wipe them out” (v. 2). [J. Robert Vannoy, Cornerstone Biblical Commentarya: 1-2 Samuel (vol. 4; Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2009), 396–399.

· “Also, an important grammatical feature in 21:6 is the phrase noting that the Gibeonites wanted שׁבעה אנשׁים מבניו (“seven men from his [Saul’s] sons”). Here one must consider the possible partitive force of the min preposition on the word מבניו (i.e., “from his sons”). While one could argue for a min of “source,” the partitive nuance of the min cannot be ruled out and appears to fit the context best. Thus, contra Campbell who suggests that this was “all” of Saul’s sons, the Gibeonites asked for seven from among them not “all” (כל) of them. Cf. Antony F. Campbell, 2 Samuel (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2005), 189–90.

[Brian Neil Peterson, “The Gibeonite Revenge of 2 Sam 21:1–14: Another Example of David’s Darker Side or a Picture of a Shrewd Monarch?,” Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament 1 (2011–2012): 201–218.

· “Thus the Gibeonites requested that justice be served by executing seven of Saul’s descendants. It is probable that the request for seven deaths carried symbolic value. Since Saul likely had been responsible for far more than seven Gibeonite deaths, blind justice might have required equal numbers of Saulides’ deaths. Mercifully, however, only a limited, symbolic retribution was requested. Saul had murdered most of the Gibeonites in their hometown, so now the house of Saul would be decimated in his hometown. Perhaps also in an attempt to create symmetry between Saul’s act and that of the Gibeonites, the request was also made that the corpses be left unburied “before the Lord.” [Robert D. Bergen, 1, 2 Samuel (vol. 7; The New American Commentary; Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 444–447.]

Five: Being sanctuary servants, living in a Levitical city, they probably know more about proper procedure in this case than anyone. They essentially request a semi-sacrificial ritual execution, to be done ‘before the Lord’ in Gebeah, for YHWH to witness the execution and lift the curse of the broken treaty.

“Normal” executions would require quick burial:

“According to Deut. 21:22, 23, persons executed were not to remain hanging through the night upon the stake, but to be buried before evening. This law, however, had no application whatever to the case before us, where the expiation of guilt that rested upon the whole land was concerned. In this instance the expiatory sacrifices were to remain exposed before Jehovah, till the cessation of the plague showed that His wrath had been appeased. [Carl Friedrich Keil and Franz Delitzsch, Commentary on the Old Testament (vol. 2; Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1996), 677–680.]

SIX: The manner of death and subsequent exposure of the bodies (and not immediate burial as would be the case in ‘simple’ murder/bloodguilt) is evidence that they understood and took very seriously the covenant penalties and sought to restore health to the land, the people, and their relationship with Israel.

· “From the context it is obvious that the bodies were exposed to the elements, and this, too, may have been an aspect of the fate of those who had violated their treaty oath (see Fensham, BA 27 [1964] 100), as elsewhere in the ancient world….

In any case, it is clear that the execution is of a special kind and that an important part of it is the exposure of the bodies of the dead. With regard to this, Fensham (1964:100) points out that exposure of the corpse was part of the punishment for a treaty violation elsewhere in the ancient Near East. [A. A. Anderson, 2 Samuel (vol. 11; Word Biblical Commentary; Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1989), 248–252.]

· “The execution took place during the first days of the barley harvest in April (i.e., in the month of Ziv). It is less likely that this event was a form of sacrifice although it may have been part of some ritual act since it was performed before Yahweh.[A. A. Anderson, 2 Samuel (vol. 11; Word Biblical Commentary; Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1989), 248–252.]

· “The comment in v. 8 that the Saulides were killed on the mountain “before the Lord” (lit., “before the face of Yahweh”) lends religious overtones to the killings but does not necessarily bring them into the category of a sacrifice, as some suggest. Rather, since Yahweh would have been invoked as a witness in the original covenant, the Lord’s presence is also sought as witness to the punishment accorded to treaty violators. [Tony W. Cartledge, 1 & 2 Samuel (ed. Samuel E. Balentine and P. Keith Gammons; Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary; Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing, Incorporated, 2001), 640–641.]

· “Seven of Saul’s descendants are therefore to be “killed and exposed” (v. 6; cf. vv. 9, 13; Nu 25:4). The Hebrew verb designates “a solemn ritual act of execution imposed for breach of covenant,” probably involving the “cutting up or dismembering [of] a treaty violator as a punishment for treaty violation” (Polzin, “HWQYʿ and Covenantal Institutions,” 229, 234; cf. Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, 266). In addition to natural calamities such as those mentioned above (plague, drought, famine, etc.; cf. Fensham, “The Treaty between Israel and the Gibeonites,” 100), Polzin singles out two other covenantal curses attested in extrabiblical sources from the ancient Near East: “The progeny of the transgressor shall be obliterated; and the corpse of the transgressor will be exposed. All three of these curses are involved in 2 Sam 21:1–14” (Polzin, “HWQYʿ and Covenantal Institutions,” 228 n. 4).

[Ronald F. Youngblood, “1, 2 Samuel,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: 1 Samuel–2 Kings (Revised Edition) (ed. Tremper Longman III and David E. Garland; vol. 3; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009), 3559–564.]

…

Cf. Robert Polzin, “HWQY‘ and Covenantal Institutions in Early Israel,” HTR 62.2 (1969): 227–40. Polzin (231) defines the Hebrew word hwqy‘ as “some kind of public ritual act of execution plausibly understood as a punishment for breach of covenant.” He also notes the close parallels of 2 Sam 21:1–14 and in the Baal Peor incident of Num 25:4. Polzin concludes that 2 Sam 21:1–14 is indeed a picture of a broken treaty where the curses are being enforced, viz., execution and dismemberment—a reality commonly included in Western Semitic treaties of this period.

[Brian Neil Peterson, “The Gibeonite Revenge of 2 Sam 21:1–14: Another Example of David’s Darker Side or a Picture of a Shrewd Monarch?,” Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament 1 (2011–2012): 201–218.]

· “One other point that highlights the importance of the notion of covenant in explaining the connection between Saul’s treatment of the Gibeonites and the famine in the land is that the punishment of Saul’s sons may also be partially attributed to a covenantal violation. Again I cite the Esarhaddon treaty which informs us that those who violate this covenantal oath should suffer the destruction of their future progeny: ‘May Zarpanitu, who grants offspring and descendants, eradicate your offspring and descendants from the land’.55 Such ideas appear within the Hebrew Bible as well (Deut. 28:55; 1 Kgs 14:10; 16:11). The exposure of the corpses in order that they might be eaten by wildlife further corroborates the fact that we are dealing with a covenantal violation. It is found within the Bible several times in reference to kings who acted against God’s wishes (1 Kgs 14:10–11; 16:1–4; Jer. 19:7), and in the Esahaddon treaty as well: ‘May Palil, lord of the first rank, let eagles and vultures eat your flesh’.56

[Joel S. Kaminsky, Corporate Responsibility in the Hebrew Bible (vol. 196; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 110–111.]

· “It is unlikely that David was merely acquiescing to the Gibeonites’ request for purely selfish motives—as an ANE monarch he had to do something to ameliorate the effects of the famine. Indeed, Fensham, Malamat, Walton, Matthews and others have clearly shown the connections between ANE curse reversal precedents and David’s actions.22 Furthermore, “sacrificial” acts in the context of covenant breach and its curses pepper not only ANE literature, but also the Hebrew Bible itself (e.g., Achan in Josh 6; Zedekiah in Ezek 17:15–16 cf. also Isa 24, etc.).23 Therefore, David’s compliance with the Gibeonites’ request is a moot point in light of ANE treaty and curse-reversal protocol. [Brian Neil Peterson, “The Gibeonite Revenge of 2 Sam 21:1–14: Another Example of David’s Darker Side or a Picture of a Shrewd Monarch?,” Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament 1 (2011–2012): 201–218.]

·

“That Saul’s progeny also remain

unburied together with the notice about the famine strongly indicates that

Saul broke the covenant that ancient Israel made with the Gibeonites (Josh.

9). This alone would explain why the nation as a whole

suffers a famine for three years. A treaty such as this one would have

been ratified by an oath that invoked curses upon each nation involved in the

agreement as a corporate entity.[

[Joel

S. Kaminsky, Corporate Responsibility in

the Hebrew Bible (vol. 196; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament

Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 108–110.

· “De Graaf (1978:182) suggests that the reason why the corpses of the slain men were allowed to remain unburied for so long was in order to let “all Israel see that something was being done about Saul’s sin” that had caused the three-year famine, and it is for this reason that they “were not removed until the first drops of rain showed that the curse had been lifted (2 Sam 21:1).” [J. Robert Vannoy, Cornerstone Biblical Commentarya: 1-2 Samuel (vol. 4; Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2009), 396–399.]

· “While we may react to this suggestion from the context of our western culture and question how or why seven innocent men should be executed to satisfy the wishes of an aggrieved people, two important truths must be borne in mind: (1) the concept of “corporate personality”—the sins of the father being visited on the children—was firmly established in the laws and customs of people in the Near East; and (2) the Benjamites had benefited from the land left vacant by the Gibeonites and had never repented of Saul’s crime nor sought to make any form of redress. Seen in this light, the request of the Gibeonites was most gracious. They could have asked for much more—a life for a life.

[Cyril J. Barber, The Books of Samuel: The Sovereignty of God Illustrated in the Life of David (vol. Two; Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 316–317.]

[We have noted above that the sons of Rizpah were most likely complicit in Saul’s actions—they would have been part of the army, as would be the other ‘official’ sons.

[We might ask why Merab’s children—with other possible Saulides around—but we have no rationale given. My guess would be that she was the most (only?) ‘official’ Saulide in the land (apart from Mephibosheth), but the request was for male descendants of Saul. And it would have been widely known that Merab was another visible case of Saul breaking solemn oaths:

“This still leaves us with the reasoning behind David’s choice of Merab’s children. Why would David choose these Saulides …? Verse 7 may give us insight into the mindset of David in this regard. In the context, the author tells us that David spared Mephibosheth on account of the “oath of the Lord” (שׁבעת יהוה) that was between him and Jonathan.38 This oddly placed notation gives the reader a possible clue as to David’s view of oath taking; viz., David keeps his vows where Saul had not. At least in the case of Merab, David’s choice of her sons may be directly connected to Saul’s lack of keeping his word or oaths to David (and others). Glaring examples appear in both 1 Sam 19:6 and 26:17–25. In the former text, Saul makes a vow (שׁבע) before Jonathan that he would not kill David whereas in the latter case Saul promised not to hurt David. Yet Saul made every attempt to kill David until he himself was killed by the Philistines (cf. 1 Sam 31). It is obvious from these examples that Saul had a problem in keeping his word and vows.39 These examples being noted, the most important instance of Saul’s failure to live up to his vows is when he refused to keep his word in giving Merab to David as a wife—not once, but twice (cf. 1 Sam 17:25 and 18:17–19).40

……………..

“In 1 Sam 17:25 the author intimates that Saul had made a twofold promise to the man who would kill Goliath: first, he promised he would give his daughter to the victor as a wife, and second, he promised to make that man’s family “free” (חפשׁי) in Israel (cf. 1 Sam 17:25).41 Although Merab is not named directly in the text, the fact that she was the oldest, as is noted later in 1 Sam 18:17, appears to be proof that she was the one in view here (note Laban’s response to Jacob in Gen 29:26). Yet we see that this promise is not fulfilled when David kills Goliath. Furthermore, to add insult to injury, not only is David not rewarded with Merab, but later David has to protect his parents from Saul’s murderous threats by spiriting them away to the land of Moab (1 Sam 22:3–4)—David and his family were far from being “free” in Israel.

….

“In the second account of 1 Sam 18, Saul once again promises Merab to David (this time explicitly, v17). …

But: “And it was when the time came to give Merab the daughter of Saul to David that she was given to Adriel the Meholathite as a wife.” [1 Sam 18.19]

So, the choice of Merab’s sons might be due to a mix of factors: she was the only remaining official blood-descendant of Saul, and all of Israel would have know that she was a living representative of Saul’s failure to keep his oaths (like in the case of Gideon).

Everybody knew what was required in this case, though it was unpleasant.

“While we may still have reservations about the propriety of executing innocent individuals for the sins of their father, let it be noted that neither David nor the Benjamites nor those selected for execution raised any objection. They understood the corporate nature of the family in Israel and believed that the request of the Gibeonites was fair.

[Cyril J. Barber, The Books of Samuel: The Sovereignty of God Illustrated in the Life of David (vol. Two; Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 319–320.